Today we present a guest post by Michael Robinson of the University of Hartford, manager of the science-and-exploration blog Time to Eat the Dogs (where this is cross-posted), and author of The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture.

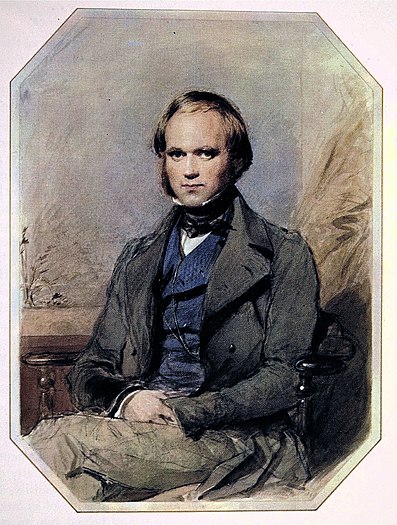

Darwin, talented naturalist.

Darwin, talented naturalist.

Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882), expert in barnacle taxonomy, lived his life as an omnivorous reader, letter-writer, and pack-rat. He attended college and traveled abroad, married his cousin Emma, and settled at Down House. There he wrote books, doted on his many children, and suffered bouts of chronic dyspepsia.

We don’t remember Darwin much for these details, eclipsed as they are by the blinding attention given to his work on evolution. But they are worth noticing if only to make a simple point. Darwin did not live life in anticipation of becoming the father of modern evolutionary biology, a status that seems almost inevitable when we read about Darwin’s life. Despite the distance of time and culture which separates us from Darwin, he lived his life much as we do: working too much, getting sick and getting better, fretting about others’ opinions, and seeking solace among his friends and family.

In spite of the scrutiny paid to evolution, or perhaps because of it, we continue to see Darwin through a glass darkly, distorted by a body of literature that, despite sophisticated analysis and a Homeric attention to details, reduces his life to the prelude and post-script of the modern era’s most important scientific theory. This is not to beat up on the “Darwin Industry” which has produced a number of superbly researched, balanced portraits of Darwin. But the nuance of such works cannot overcome the weight of Darwin as a mythic figure in the popular imagination.

So what should we remember about Darwin?

He was not the “father” of evolution. The idea that species could change over time had a long history that predates Darwin. “Transformism,” as it was called, had many adherents including French naturalists Comte de Buffon and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. Even Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, took up the cause, defending the idea in his book Zoonomia (1794-96). But by the mid 19th century, transformism carried with it the whiff of quack science and radicalism. For the empirically-minded European naturalist, accepting transmutation of species was akin to believing in Sasquatch, an idea made all the more unpalatable because it brought with it an uncomfortable proximity to lower social classes and leftist political causes.

Darwin’s reputation rested on different grounds. He did not become the buzz of London because he supported transformism. Rather, he brought to the defense of transformism a stunning, almost overwhelming, body of evidence. In Origin of Species, published in 1859, Darwin gathered his data from a number of different fields: comparative anatomy, taxonomy, biogeography, geology, and embryology. Darwin had come to the idea of evolution relatively early in his scientific career. A sketch of an evolutionary tree appears in Darwin’s notebook in 1837. But Darwin kept his views close to his chest, amassing arguments and pieces of evidence over the next twenty years.

But this wasn’t the only reason why Darwin’s monograph flew off bookshelves faster than The Da Vinci Code. Origin of Species posited an entirely novel mechanism of evolution, natural selection, which explained why species change over time. According to Darwin, all populations quickly outgrow the ability of their environments to sustain them. Ultimately individuals of a species are forced to compete with each other for limited resources, winnowing the ranks of survivors to those who are best adapted to the conditions around them. These survivors pass on their successful traits to their offspring and change the constitution of the population accordingly.

Sounds tidy enough, but natural selection had to compete with a number of other possible mechanisms for evolution. For Buffon, species “degenerated” over time, moving away from their original form. For Lamarck, species changed when individual organisms become modified during their lifetimes and passed down these modifications to their offspring (also know as the inheritance of acquired characteristics). For others, evolution showed the handiwork of the Creator who nudged species, humans in particular, up the ladder of perfection.

In today’s world of creationist parks, polarized school boards, and dueling fish decals, the battle line has been drawn over the idea of evolution. Do species change over time? This is the question that sends evolutionists and biblical literalists charging down the hill at each other like the kilt-clad armies of Mel Gibson. But this was not always the case. In Darwin’s day, evolution had broad (though not universal) support from naturalists as well as liberal members of the clergy.

It was not evolution but natural selection which ruffled feathers. For many nineteenth-century Britons, natural selection seemed Deist at best and nihilist at worst. After all, what room did Darwin allow for God if nature was doing all of the selecting? As a result, many chose to believe in a theistic or “teleological” version of evolution which accepted Darwin’s evidence for evolution but rejected the mechanism he thought lay behind it.

To be fair, even Darwin had his doubts about whether natural selection could explain all aspects of species change. Later editions of Origin of Species left the door open to other mechanisms of evolution, particularly the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Only in the early twentieth century did natural selection finally win the day among professional scientists.

All of this had led some modern critics of Darwin to point out that his work falls short of certainty, that gaps in the evidence,particularly in the existence of intermediate fossils, doom the ideas of Origin of Species to the status of theory. Nothing about this charge would have upset Darwin. Indeed, he said as much himself in Origin of Species, devoting sections of the book to “Difficulties on Theory,” and “The Imperfection of the Geological Record.”

Where critics see lemons, Darwin saw lemon meringue pie (recipe circa 1847). While Renaissance scholars once aspired to certainty in the study of nature, this had changed by the 19th century as naturalists realized that the “see it with my own eyes” standard of proof worked poorly in trying to understand phenomena that took place far away or in the deep past. Indirect evidence could never yield certainty, but it could be used to develop provisional ideas that gained or lost strength on their ability to account for new data. By this standard, Darwin’s two theories, evolution and natural selection, have held up amazingly well over the past 150 years. That Darwin seemed comfortable in accepting his work as “theory” may seem like evolution’s Achilles heel to Creation Scientists and Intelligent Designers, but it is feature which places his research firmly within the era of modern science.

Michael recommends for further reading, The Politics of Evolution by Adrian Desmond, and The Creationists by Ron Numbers. On Darwin specifically, Janet Browne has written a “terrific and accessible” two-volume biography (entitled Charles Darwin). For those looking for a quicker run-through, I can recommend Browne’s distillation: Darwin’s Origin of Species: A Biography.