I’m a little hesitant to include Jed Buchwald’s Rise of the Wave Theory of Light (1989) in my physics canon, not because of any flaws in the book—it very nicely accomplishes what it sets out to do—but because it’s so focused on its argument concerning the rise of the wave theory. This means it focuses tightly on people directly involved with the rise of the wave theory, notably Augustin Jean Fresnel, and leaves some other important figures, Thomas Young for example, at the margins.

I’m a little hesitant to include Jed Buchwald’s Rise of the Wave Theory of Light (1989) in my physics canon, not because of any flaws in the book—it very nicely accomplishes what it sets out to do—but because it’s so focused on its argument concerning the rise of the wave theory. This means it focuses tightly on people directly involved with the rise of the wave theory, notably Augustin Jean Fresnel, and leaves some other important figures, Thomas Young for example, at the margins.

Since we haven’t done the Canonical series in a while, it’ll be useful to refresh the point of the exercise. It is not to offer a “best of” in history of science writing or argumentation; rather it is books one can concentrate on to get a good, sophisticated overview of what happened in history. Thus, reading Buchwald’s book, one should be aware that one is getting an explanation for the rise of the wave theory, not a history of the wave “idea”, or a tour of early 19th-century optics, which would be most useful from the “Canonical” perspective. But, seeing as I know of no other book that covers the subject in a detailed and sophisticated way, canonical Rise of the Wave Theory of Light shall be. We can always go back and replace it, or supplement it with a journal article or two, at a later date.

The bulk of the action in the book takes place between 1810 and 1830, which, readers should be aware, stretches across a fault line in the history of physics (i.e., read Warwick and early chapters of Jungnickel & McCormmach first; and probably something on “rational mechanics” in France that we haven’t covered here yet). It is in this period that precision and mathematical theory come to a large number of new subjects in physics, such as electricity and magnetism, essentially annexing them from the wider world of 18th-century natural philosophy. Optics is sort of among these subjects. Optics had, like astronomy, been among the geometrical sciences rooted in antiquity; but had not, unlike astronomy, been part of more recent developments in super-precise observation and sophisticated mathematical analysis. Circa 1800 that started to change, and that augured a sea change in how physicists thought about light, moving from the idea of light as being physically made up of discrete parts, to light as being waves in an all-pervading medium.

I’ll leave the specifics of the narrative to Buchwald. What I’d like to do is take the opportunity to look at some of Buchwald’s argumentative strategies, which are fairly rare in the history of science, but I think are important to discuss because they are powerful in specific ways.

As I mentioned in my Fresnel post, compared to a lot of the other historians we looked at in grad school, Buchwald always seemed awfully fussy. What I mean by this is that there is a strain of the history of science where historians are interested in all the nitty-gritty of what, say, Newton was thinking when he constructed such and such an argument concerning the orbits of comets, or some such. Lots of equations, not much historical consequence. The word usually used to describe this sort of detail-mongering is “antiquarianism”. Christopher and I have taken to referring to it as “wonky” history. And, indeed, Jed Buchwald is a chief editor of one of the wonkiest of all history of science journals: Archive for History of Exact Sciences.

But Buchwald isn’t simply a history of science wonk for the sake of it. He seems to choose his topics carefully to see where a wonky treatment can lend the most illumination. In particular, Buchwald is interested in what possibilities are engendered in certain kinds of arguments, regardless of whether historical actors were aware of, or could fully articulate those possibilities. In the case of the wave theory, it mattered what theoretical suppositions concerning the physical character of light one used in cases where one used mathematical theories to describe certain kinds of experimental phenomena. In this way, Buchwald becomes a critic not simply of the social relations between scientists, but, probably more importantly, of the character of the science itself, what it could and could not accomplish, and what conceptual distinctions needed to be drawn for further developments to occur.

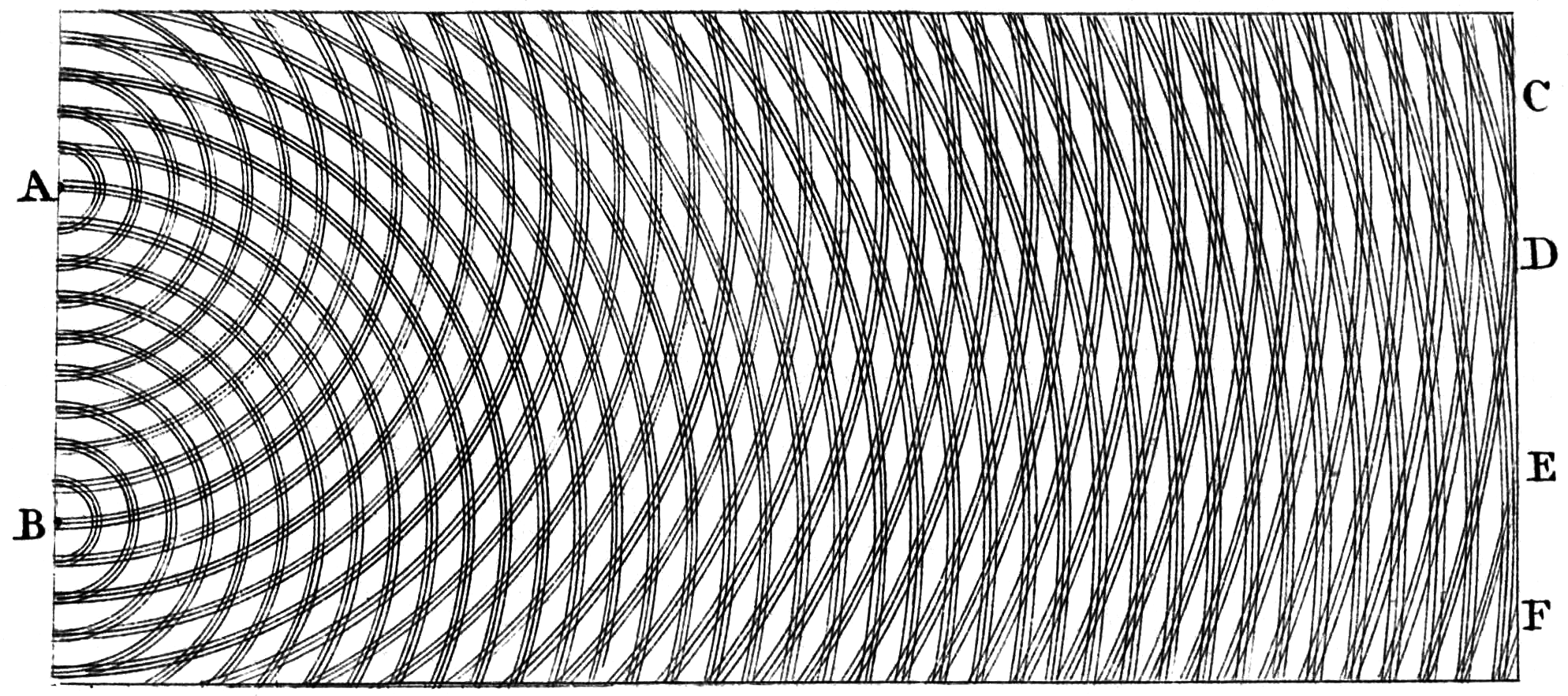

Thomas Young sketch of interference effects, 1803

Thomas Young sketch of interference effects, 1803

Buchwald’s methodology puts some space between him and the historical actors, and brings him in close to the physical argument. For example, while diffraction effects, such as those demonstrated by Thomas Young, were often presented as an important argument for wave theories, Buchwald is able to argue against the importance of diffraction as a crucial issue, only through a painstaking reconstruction of ray-based mathematical theories, which were only ascendant for a couple of decades in the early 1800s. Instead, Buchwald argues, it is a series of advanced experimental polarization phenomena that only waved-based theories could explain, that was able both to strengthen wave proponents’ convictions in their own arguments, as well as ultimately to convince others of the importance of their approach.

Those who did not recognize the point (such as David Brewster) were inevitably left behind once the power of the new theory was accepted. While Buchwald certainly recognizes that commitments to either a particulate or a wave program were important, what makes his story really powerful is the way he demonstrates how the failure to articulate or understand the kinds of arguments being mathematically articulated allowed physicists of this era to talk past each other on crucial points. This, I think, is a good demonstration of what I mean by philosophy informing historical accounts. Buchwald uses a sophisticated philosophical understanding of what was going on to pinpoint why actors took the positions they did, and—in an unusual move for a historian of science of the new era—to suggest specifically why the more philosophically sophisticated theory could win out, provided the methodology was accepted.

The history one gets from Buchwald has a spare aesthetic: he is interested in what he judges matters to his specific account. For example, Buchwald brushes to the side differences in natural philosophical ideas concerning the particulate idea of light because the only difference that really mattered historically (and mathematically) was whether light rays were discrete entities. However, the spareness of the aesthetic doesn’t prevent Buchwald from being fully alive to the possibilities in the historiographical innovations that came up especially in the 1980s.

Notably, Buchwald understands that to accept the decisiveness of Fresnel’s and his allies’ account, it was necessary to subscribe not only to the possibility of the wave theory, but also to the then-novel requirement that aligning mathematical arguments with precision experimentation could decide between rival physical theories. The gradual acceptance of this alignment was one of the most important trends in physics of that era, and it is probably the thing of most general importance that Buchwald’s book illustrates from the ground level.

Accepting the methodology was not necessary to taking up the wave theory: François Arago, one of Fresnel’s allies, did not tend to mathematize his arguments, leading him to fall quickly behind the pace of Jean-Baptiste Biot on the matter of chromatic depolarization, a blow to Arago that gave him incentive to support Fresnel against Biot’s particle-based theories. Still, accepting the methodology would prove decisive: it was mainly only with the rise of the Cambridge theorists in the 1830s, who became major propagandists for the wave theory, that Fresnel’s work was ultimately accepted as crucial. Other physicists did not need to accept the wave theory thereafter, but they could not participate in new developments unless they did so.

Both details and context matter to Buchwald, but expect him to spend time on them only if they matter. This book is a historical argument, and not, unlike, say, Warwick, a more leisurely stroll through an intellectual milieu. While both Warwick’s and Buchwald’s books are simply great, ultimately I personally prefer Warwick, because while sometimes he stops for an intense look, sometimes he just stops and looks around, which is just as important for progressive history writing.