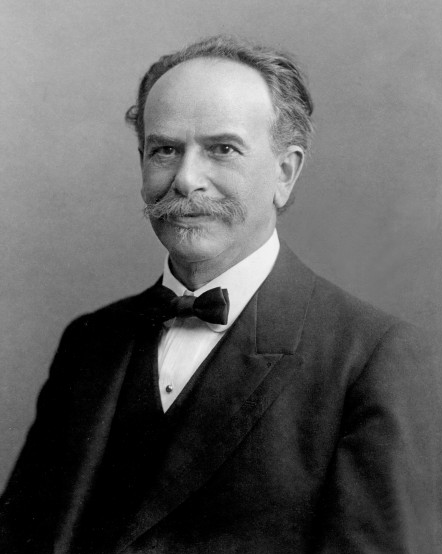

Franz Boas

Franz Boas

Franz Boas’ (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) The Mind of Primitive Man occupies a cherished place in not only the anthropological canon, but also in anthropology’s disciplinary self-understanding. In its 1938, expanded edition, Boas’ chapters provide a very interesting glimpse at the landscape of ideas which defined early 20th century ethnography and other social sciences.

One of Boas’ most difficult chapters was the fifth, titled: “The Instability of Human Types.” The roots of this chapter lay in his landmark 1916 essay, “New Evidence in Regard to the Instability of Human Types.” Building on the claims of not only his work on immigrants and H. P. Bowditch’s important, though forgotten, 1877 study, “The Growth of Children,” he concluded that not only was human stature variable, but more importantly, there existed variability in both the cephalic index and the width of the face. This led him to consider how far the bodily features of man can be modified by so-called physiological changes brought about by conditions in the physical and social environment.

He found that when conditions of growth and nutrition are favorable there was an increase in stature and modifications to the “head form.” These modifications were on the same level as the difference between “races and sub-races which have been distinguished in Europe” (PNAS, 1916, 714) These changes, moreover, did not in any way affect the “germ,” so that upon return to their old environments, individuals would revert to their old type. Note here that Boas is not arguing that there are no “types.” He is merely contending that these types are subject to a degree of modification through physiological changes brought about by the environment.

Under many circumstances, moreover, the genetic type will “exert its influence” as by any standard the “head-form of the Northern Italians is excessively short” (715). However, even intermarriage and “admixture” between two types does not account for the physical characteristics of existing populations:

The modern Porto Rican is short-headed to such a degree that even a heavy admixture of Indian blood could not account for the degree of short-headedness. If we apply the results of known instances of intermixture to our particular case, and assume stability of type, we find that, even if the population were one-half Indian and one-half Spanish and Negro, the head-index would be considerably lower than what we actually observe. There is therefore no source that would account for the present head-form as a genetic type; and we are compelled to assume that the form which we observe is due to a physiological modification that has occurred under the new environment (717).

In the 1938 edition of The Mind of Primitive Man has a much more developed series, and was much more firmly, environmentalist (to a point). Boas noted that “domestication” was of great importance for both humans and animals, with the advent of settled agriculture as well as fire and tool making had effected the physical and intellectual development of mankind (78-85). The changes wrought by the domestication of the human species was a fantastic example to Boas of the “direct influence of environment,” (85) where much evidence demonstrated that the form of a species was “determined by environmental causes” and was not considered to be “absolutely stable or subject to accidental variations, but as determined in definite ways by conditions of life” (86).

Immigrants, among them Italian and Puerto Rican, demonstrated differences in head-form, from their foreign-born parents due to changes in environment, particularly nutrition. He cautioned, however that “it would be erroneous to claim that all the distinct European types become the same in America, without mixture, solely by the action of the new environment.” However, the history of “of the Dutch in the East Indies, of the Spaniards in South America, favors the assumption of a strictly limited plasticity” (95). This is a puzzling claim that is not really pursued.

Puzzling too is Boas’ account of selection. “Selection,” Boas concluded, “acts primarily through social stratification. It is not immediately dependent upon bodily form” (97). He continued, “I know of hardly any example that proves beyond cavil the direct influence of selection in the sense that morbidity, fecundity , migration, and selective mating have been proved to be solely dependent upon healthy bodily forms” (98).

What Boas meant by selection in this context referred to an important ethnological and sociological debate over the origins and nature of “selective disassociation.” G. P. Watkins, in his article for the Popular Science Monthly, defined this term as occurring “where individuals of more or less similar traits are segregated from others and put into a special environment,” which differentially affects their survival through the introduction to new environmental conditions. Watkins noted that an excellent example of selective disassociation was “international migration” in the case of the settlement of the American colonies by a particular ethnic group (80-81). Many turn of the century sociologists observed that the city subjected a newly defined and isolated group (disassociation by displacement) to a particularly high mortality rate (or lethal selection).

What Boas found objectionable were the arguments of Vacher Lapouge and Carlos C. Closson, that certain ethnicities or “types” were more disposed to migrate from the country to the city due to some hereditary predisposition. Disassociation by displacement or migration was (for Boas as well as Lapouge and Closson) the primer of social selection, establishing the conditions under which society could work its influence upon existing types.

Quite interestingly, Boas and Lapouge and company all agreed on the phenomenon of “social selection.” Closson gave a sensible definition- “the selective forces at work in human society” (Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1896, 159) which affected mortality and fertility. Closson believed that dissociation by stratification (social stratification) and dissociation by displacement (internal migration) were due primarily to factors of racial psychology, where migration and social stratification had to do with the “blond” “long-headed” race being more adventurous and more prone to social domination. Boas thought primarily social factors were at work for the composition of cities and distinctions between classes. This is, mostly, what William Z. Ripley argued.

Ripley sniffed (and this provoked a bit a feud with Closson, who, in turn toned down his emphasis on racial psychology):

From the preceding formidable array of testimony it appears that the tendency of urban populations is certainly not toward the pure blond, long-headed, and tall Teutonic type. The phenomenon of urban selection is something more complex than a mere migration of a single racial element in the population toward the cities. The physical characteristics of townsmen are too contradictory for ethnic explanations alone. A process of physiological and social rather than of ethnic selection seems to be at work in addition. To be sure, the tendencies are slight; we are not even certain of their universal existence at all…..Naturalists have always turned to the environment for the final solution of many of the great problems of nature. In this case we have to do with one of the most sudden and radical changes of environment known to man. Every condition of city life, mental as well as physical, is at the polar extreme from those which prevail in the country. To deny that great modifications in human structure and functions may be effected by a change from one to the other is to gainsay all the facts of natural history (The Races of Europe, 599)

He and Boas contended that the environment wrought a decisive physiological influence upon individuals which lead to modifications of the existing type. Both too contended that social forces greatly affected the mortality and fertility of populations already placed in different conditions than their fellows by virtue of migration to the cities and residence within definite locales of the urban environment. “Urban selection” meant a great “sorting” which had little to do with physical characteristics and racial psychology. It was the city with its distinct institutions, customs, and mores, which rewarded those who are able to best adapt to the new conditions (554). Ripley did not believe type to be unimportant, but like Boas, he believed that environment wrought great changes to stature. This explained his emphasis on the degenerating effects of city life, a concern Boas did not share. This was why Ripley believed that the study of races was primarily archeological, while discussions of the present were sociological.

The city as the greater sorter, as a selector, and as a laboratory for society was a frequent trope. Adna Ferrin Weber wrote in the The Growth of Cities in the Nineteenth Century: A Study in Statistics (1899):

The city is the spectroscope of society; it analyzes and sifts the population, separating and classifying the diverse elements. The entire progress of civilization is a process of differentiation, and the city is the greatest differentiator. The mediocrity of the country is transformed by the city into the highest talent or the lowest criminal. Genius is often born in the country, but it is brought to light and developed by the city. On the other hand, the opportunities of the city work just as powerfully in the opposite direction upon the countrymen of an ignoble cast; the boy thief of the village becomes the daring bank robber of the metropolis.

While Boas and Ripley have been put into separate historiographical camps, with Ripley being on the wrong side of the divide of anthropological modernity, their emphasis on the plasticity of type due to social and psychological conditions was similar (even if Ripley was cautious in his language.) Thus, while remembered as one of the most prominent and last of the anthroprometrics, Ripley considered himself, at least cautiously, as an urban sociologist like Adna Weber and as a “naturalist” like Montesquieu.