In my various conversations about my Joseph Agassi series, as well as most importantly here (email and otherwise), I have been challenged on the idea of “intrinsic value”: do ideas have value, can any idea be useful for politics and conversation; or are ideas simply to be explained rather than used? Does our ever-increasing knowledge of the complexity of past ideas and intellectual movements allow us to say that our understanding of ourselves and our world has improved from, say, the 19th century?

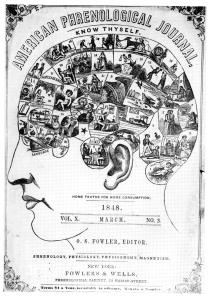

Of course, the answer is yes. Science has progressed; the question is whether there are rules (or even hints to the forces or interests) responsible for the progress of science. Philosophers and historians of ideas also know this. No one today would defend phrenology as a science. Neurology is now the science of the brain. Is neurology superior to phrenology? Yes, but I would very much like to hear an argument to the contrary.

What separates the philosophers from the historians and sociologists of science is the degree to which philosophers (at least the diminishing numbers who are flexible rationalists like Mary Hesse) cautiously affirm that one of the tasks of the philosopher is to decide what intellectual inventions are worth keeping (tolerance, for example, or the non-random nature of scientific inference, to take another) and perhaps say something about how good ideas come about, as opposed to bad ones, which hopefully do not last.

However, just because phrenology is now not a science does not mean that one can not learn about it and hazard some arguments about the connection between science and social context and how we differentiate between “good” and “bad” ideas. Can we say really that phrenology was a “bad” idea? Yes. But how to explain it? That is much harder.

One can also condemn phrenologists for their odd ideas which appear nonsensical now. But in order to learn something from phrenology, we should in a sense suspend judgment, if just for the moment. We can always judge later. We can always condemn phrenologists after we have explained some of their ideas. Condemnation is quite easy, explanation trickier.

To start, we can say that phrenologists were in error, as Agassi would. Error is not an absolute standard and error is not a bad thing by necessity; errors are frequently productive. Did phrenology lead to any productive errors? This is a good question. Can we look at nineteenth-century psychology and the brain sciences and say that phrenology in the hands of its critics led to good ideas and some lovely take-downs (for example in the works of Alexander Bain in his On the Study of Character: Including an Estimate of Phrenology (1861)? Yes.

Bain addressed phrenologists like Agassi treats everyone, from fanatics to Paul Feyerabend: much can be learned by understanding that, though the phrenologists were in error, they nonetheless considered their study to be rational and systematic. Phrenologists were totally convinced in the consistency of their ideas. From the view of the outsider, of course, the inconsistencies show. Nineteenth-century ideas are a bit like customs in this way.

Since phrenologists understood their ideas as rational, we must uncover their logic. Understanding the argument (however strange) means that we must try to divorce as much as possible the rhetoric from the ideas. Next, all erroneous ideas are interesting, but not all ideas and musings are to be treated equally seriously. Must we read everything with equal seriousness? No. Is there a core set of assumptions that we must take seriously for every 19th century belief system? Yes. This if anything is a manifesto for the study of the ideas of the nineteenth century.

Finally, reducing weird ideas like phrenology to happenstance or social pressure, by demarcating reason and values, forces us to think too much of rationality. It allows us to scapegoat social life. It allows us to excuse error by reducing it to social pressure. It does not as hard questions of what it means to be rational. Does thinking logical, consistently, moving from evidence to evidence produce good theory? Not always, as exhibited by phrenology.

Also, just because phrenologists are rationally consistent does not mean everything they write can be explained via rational principles and argumentative logic. Ideas do have a social component, and ideas are deeply personal. Agassi declares in his philosophical anthropology, “Assuming too much rationality is silly.” Within every ‘school,’ many differences and eccentricities are not really subject to full explanation: taking ideas seriously means that at most we can explain most ideas and their significance, we need not explain every element of a foreign belief system (is this one of the failings of anthropologists, I wonder?). Intellectual history should be defined henceforth by modesty. We only need to explain elements of an intellectual system. Explaining part of something well is better than explaining all of it poorly.

Relativists and social constructivists both hold that customs and social life cannot be explained by appeal to universals or to rationality (or the great myth of human nature) because of their particular natures. Both camps are giving in to the dichotomous series that everything which is not particular is general, that everything which is not natural is social, and that social life, by not having anything to do with nature, can only be explained through reference to particulars. Anthropology and the history and sociology of science, being placed in such constraints, find their work very easy, as they need not explain anything.

How does one actually explain the particular? This is a variation of the is and ought problem of moral thought. Further, the rejection of universals and the reduction of everything to particulars (or grammar) is “anti-philosophy.” More: relativism is the ultimate reductionism. (Both Agassi and Mario Bunge hold this; Bunge would add that philosophy must have ontology, metaphysics, and a theory of positive evidence—the last most importantly in disagreement with Karl Popper.)

Pace, phrenology as a social construct can only be explained in reference to social particulars (and something that weird can only be explained as an imposition upon nature) and not to any kind of reasoning process. Of course, phrenologists would never say that they were being anything less than rational. We should believe them. Phrenology is thus like the customs of anthropologists, consistent to its adherents and shown to be error-ridden by outsiders.