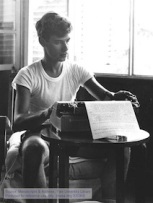

David Apter in 1953 at University College of the Gold Coast at Achimota. Photo by Eleanor Apter. Click for a larger version at the Apter Collection of photographs at Yale University Manuscripts and Archives

David Apter in 1953 at University College of the Gold Coast at Achimota. Photo by Eleanor Apter. Click for a larger version at the Apter Collection of photographs at Yale University Manuscripts and Archives

Clifford Geertz’s well-known 1964 essay, “Ideology as a Cultural System” appeared in a volume called Ideology and Discontent, which was edited by David Apter (1924-2010). Apter (you might recall from this post) was a modernization theorist. His best-known work on the subject was The Politics of Modernization (1965). The appearance of Geertz’s essay in Apter’s volume should be no surprise since Geertz was himself a scholar of modernization, and served with Apter as a member of the University of Chicago’s Committee for the Comparative Study of New Nations. (Relevant here is Geertz’s long discussion near the end of his 1964 essay on the political culture of newly independent Indonesia.)

Apter’s own introductory essay in the volume (titled “Ideology and Discontent,” pp. 15-46) is a discussion of the relationship between economic development, political ideology, and social science, and is very much in the tradition of the intellectual liberalism of that era. But it also zigs in certain places where you might expect it to zag, and, though it is not as lucid or valuable as Geertz’s essay, it is very much worth a read to try and get a beat on some of the contours of the kind of critical-interpretive social science in which Apter was engaged. Additionally, it is the earliest reference I have so-far come across to the “ideology of science,” which is a concept I have been tracking off and on through this blog (though Google Books informs me there are a number of earlier precedents).

First and foremost, as with Geertz’s essay, the concept of “ideology” was not intended as a term of condemnation, nor did it necessarily imply delusion. For Apter, “ideology” meant political ideology, and ideologies were adopted as a sociological response to societal change: ideology “links particular actions and mundane practices with a wider set of meanings and, by doing so, lends a more honorable and dignified complexion to social conduct” (16). It could be regarded as serving two sociological and psychological functions: first, to foster “solidarity” (a function “first made explicit by Marx,” and further theorized by Georges Sorel (1847-1922) through the concept of the “myth”); and second, following Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) and Erik Erikson (1902-1994), to foster a sense of personal “identity,” particularly in the youth of a society.

Ideology, however, was also a troubling subject. Unlike Daniel Bell (1919-2011), who had proclaimed the “end of ideology” in 1960, Apter followed Karl Mannheim (1893-1947) in observing that it appeared to be impossible to analyze ideologies from a non-ideological point of view (39). His thinking on this point (like Geertz’s, but unlike Erikson’s) did not constitute a sort of post-Marxist realization that all thought, including scientific thought, was tied to one or another socio-politico-cultural perspective. Rather, Apter’s position was that there existed a distinct “social-science ideology” (16), which created a kind of conflict of interest in that representatives of that particular ideology were intellectually responsible for analyzing all other ideologies as well.

Thus, Apter wrote, “ideology is not quite like other subjects. It reflects the presuppositions of its observers. The study of ideologies soon draws one into the analysis of social science itself, into meta-analysis” (16). He elaborated (17-18):

[The] study of ideology reveals the ‘scientific’ status of social science more clearly than does any other subject. To study about ideology (as distinct from examining specific ideologies) raises issues about the scientific quality of social science methods. These issues are: the role of the observer—aloof social scientist or passionate but reflective participant; the degree to which we can assume the motivations and attitudes of others by ’empathizing’ with their roles or playing similar ones; the degree to which we can separate observer roles from previous ideological commitment, or put more generally, the problem of bias in research; and the nature of prediction.

Indeed, “to consider ideas about science in the context of ideology does not make ideology scientific—but science ideological” (35).

This was a problem because the social scientist was an increasingly powerful figure in modern society: “Ready or not, social scientists are being asked to do research leading to policy formation. What happened first in the natural and physical sciences is now beginning in the social sciences—that is the modification of change through the application of planning and control” (18).

For Apter, the political ascendancy of the social scientist was an ideological consequence of economic development. The bulk of Apter’s chapter was occupied with a consideration of ideological shifts in societies as they developed, which he saw in a similar way as other modernization theorists. “Rightly or wrongly,” Apter wrote, “I visualize developing communities as if they were strung on a continuum. The new developing communities are trying to sort out certain problems that the older ones have more or less resolved, although not in all cases. These problems involve the more ‘primordial’ sentiments based on race, language, tribe, or other factors, which, although not relevant to the development process, may be relevant to the maintenance of solidarity or identity.” By contrast, in “the highly developed communities, such primordial sentiments are less a problem than are confusion, irresponsibility, withdrawal, and cynicism” (22).

Market scene in Kampala, Uganda, 1955-56. Photograph by David Apter. Click for a larger version at the Apter Collection of photographs at Yale University Manuscripts and Archives

Market scene in Kampala, Uganda, 1955-56. Photograph by David Apter. Click for a larger version at the Apter Collection of photographs at Yale University Manuscripts and Archives

Apter identified “socialism” and “nationalism” as the key ideologies at work in the modernization process. Unlike, say, Walt Rostow, he did not regard socialism as a pathological form of modernization. Rather, socialism functioned to enable political leaders in developing areas “to repudiate prevailing hierarchies of power and prestige associated with traditionalism or colonialism. Furthermore, socialism helps to define as ‘temporary’ (as a phase in economic growth) the commercial ‘market place’ or ‘bazaar’ economy.”

Whatever particular form socialism might take (Apter pointed out that socialist rhetoric in many African countries had little to say on the subject of private property or religion), it placed “an emphasis on ‘science’—science for its own sake as a symbol of progress and as a form of political wisdom.” It also placed “an emphasis on development goals, for which individuals must sacrifice.” Ultimately, “Socialism is viewed as more rational than capitalism because of its emphasis on planning—more scientific, more secular, and more in keeping with the need to fit together and develop functionally modern roles” (23-24).

Of course, socialism was not an inevitable ideology: Apter pointed to the unusual Japanese employment of a nationalist ideology in the course of its own modernization. But nationalism more typically constituted a reaction to socialism in the course of the struggle for political independence and economic modernity. “Nationalism incorporates specific elements of tradition and employs them to bring meaning to the establishment of a solidly rooted sense of identity and solidarity,” and “allows primordial loyalties to serve as the basis of the society’s uniqueness.” In a nationalist period, “the main structure of society is accepted as it stands while greater opportunities are sought. It is ‘radical’ in only one political context, colonialism” (26). Thus, in the difficult process of modernization, nationalism and socialism were apt to exist in a “dialectic” (26).

Apter’s illustration of the “dialectic” between nationalism and socialism in the course of development, “Ideology and Discontent,” p. 27.

Apter’s illustration of the “dialectic” between nationalism and socialism in the course of development, “Ideology and Discontent,” p. 27.

The diminishing of both socialism and nationalism at the end of this process represented the ascendancy of the “social-science ideology”. According to Apter, “Advanced development communities are no longer in the process of changing from traditional to modern forms of life. As a consequence, they look beyond programmatic ideologies with their simplified remedial suggestions. One of the outstanding characteristics of such communities is broad agreement on fundamentals and corresponding magnification of minor issues.”

But developed communities had their own problems, which revolved around the ascendancy of a professionalized bureaucracy, which Apter also referred to as “a scientific elite” (30). The ascendancy of this elite, in turn, created “a large proportion of functionally superfluous people, particularly in unskilled occupations, and by that,” he meant, “those who are largely unemployable” (31). This “bifurcation” of society represented a major challenge to democracy, which should sound familiar to people in science studies (31):

Any political conflict quickly becomes a problem of evaluating evidence. Each interested body employs its own experts to bring in findings in conformity with its own views. Laymen must decide which expert advice to accept. But the expert has been involved in the decision-making process. What happens to the nonexpert? Too often he cannot follow the debate. He withdraws, and the resulting bifurcation is more complete than one might ordinarily imagine. Modern society is then composed of a small but powerful group of intellectual participant citizens, trained, educated, and sophisticated, while all others are reduced in stature if they are scientifically illiterate.

This trend, needless to say, put social scientists in an awkward position. Their “ideology” was unusual in that it was “not polemical” and that social scientists were “the first to warn of the inadequacies of their discipline when applied to social problems” (35-36). Yet, in modern development communities, governments took on many new responsibilities, and therefore routinely sought social scientists’ advice, placing them in a position of immense power. They not only became divided from the rest of society, the social scientist was the person who “penetrates all the disguises created by the untrained mind or the ideological mind and attaches himself to the image of the wise. He represents the ‘establishment'” (37-38).

Looking close to home, Apter asserted, “The United States has clearly opted for science, and precisely because it has done so it must take the consequences” (37). According to Apter, these consequences mainly involved having to deal with political conservatives, and particularly the vitriolic and racist rhetoric of the radical right (38, Apter’s emphasis):

Today’s American ideologue is a middle-class man who objects to his dependence on science even when he accepts its norms. He is resentful of the superiority of the educated and antagonistic to knowledge. His ideology is characteristically not of the left but of the right. It is, in extreme cases, of the radical right, looking back to a more bucolic age of individuality and localism, in which parochial qualities of mind were precisely those most esteemed—to a simple democracy in fact. Robbed of its individuality, the middle-class ‘disestablishment’ forms loose associations with others who are escaping from the fate of superfluousness. Social hatred is directed against the Negro, the black enemy who can destroy the disestablished, and against the Negro’s protector, the establishment man whose belief in rationality and equal opportunity has altered the system of power and prestige so that it is based on universalistic selection and talent. Today, the radical right fights against the bifurcation of society on the basis of talent. It is the resistance ideology of all those who hitherto were the Stand figures of our society in an earlier day; the models of once sober, industrious, and responsible citizens.

In 1964, this was a typical, if somewhat idiosyncratic, expression of liberal thought. Two years earlier, liberal historian Richard Hofstadter first published his study, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. In 1964, the political emergence of modern American conservatism with the presidential candidacy of Barry Goldwater required diagnosis. (One of the essays in Apter’s volume was a study of the American radical right.) It was, furthermore, obvious to cosmopolitan intellectuals that they, or people like them, were in positions of power, and that they were in league with America’s professional classes. Finally, with the postwar decline of Marxism on the American left, the notion that another sort of challenge to the “establishment” might arise from that side of the political spectrum seemed remote.

Apter’s view did not represent a “faith” in social science; he understood its political position to be problematic. Yet, it was difficult to imagine an alternative path. Violence and dissent seemed possible, but the “more hopeful alternative,” he wrote, “is the spread of social science. It is in this sense that we can say that social science has become the ultimate ideology and science the ultimate talisman against cynicism” (39). His recommendation for the future was further study. “We need to understand problems of solidarity and identity more clearly. A kind of settling-down process is in order. With respect to ideology, social science differs from all others in one respect. The only antidote for it is more of it, addressed to solidarity and identity problems” (41).

It is a curious academic position, at once antithetical to later views, which would turn away from invocations of science and elitism, yet very akin to them in its prioritization of the need to study problems of ideology and identity in order to salve persistent social ills.