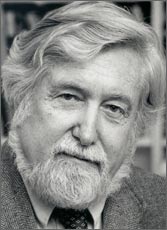

Clifford Geertz (1926-2006)

Clifford Geertz (1926-2006)

I suspect most historians, including myself, could not say much about the anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s work and ideas beyond the two-word phrase “thick description”. Yet, almost all historians will know at least that much. Further, although he borrowed the phrase from Gilbert Ryle, these historians will likely associate the phrase with Geertz, probably because at some point they have read his 1972 essay “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight”. As an undergraduate history major, I was assigned it as part of my senior year methods course.

I would argue that most historians know about thick description, as exemplified in “Deep Play”, because it has become integral to our sense of professional identity. It articulates what we have the ability and freedom to do, which others cannot (or, for ideological reasons, do not) do. This identity identifies historians as reliable experts at getting beyond the surface features of a culture and teasing out the hidden values and presuppositions lurking within its more visible elements: its texts, its propaganda, its day-to-day practices, its objects, and so forth.

Unfortunately, this skill is often treated as a kind of secret, to which historians simply gain access upon induction into the historians’ guild by reading works like “Deep Play”. Once in, you need not worry too much about what actually constitutes legitimate and valuable interpretations of past cultures. (My bête noire is historians’ continued belief that “scientism” and “technological enthusiasm” constitute legitimate characterizations of the rationales in certain technical and political cultures.)

We could doubtless benefit from reading more of Geertz on the proper interpretation of culture. This post is about his essay, “Ideology as a Cultural System,” first published in Ideology and Discontent, ed. David E. Apter (Free Press of Glencoe, 1964), pp. 47-76, which still bears sober reading a half-century later.

Read More…Read More…