The real roadmap for postwar science?

The real roadmap for postwar science?

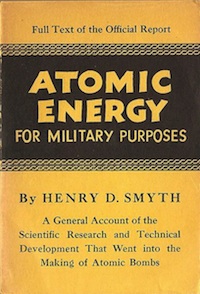

In August 1945, the sense that the war held important lessons for how peacetime science should be organized was dramatically augmented by the atomic bombing of Japan, and the release of the Smyth report, detailing the massive collective scientific and engineering effort that went into producing the bomb.

In an editorial entitled “The Lesson of the Bomb,” published August 19, 1945—a week after the Smyth report’s release—the New York Times immediately spelled out the ramifications. It observed, “The Western democracies at least have been rudely awakened to what the ‘social impact’ of science means. Books enough have been written on the subject, but it took the bomb to make us realize that the discussions were not just academic.”

The Times noted that scientists had always organized scientific conventions to share their work, “This time they were organized to solve an urgent problem. They solved it not in the fifty years expected before the war but in three, and they solved it so rapidly because they were organized and competently directed. Why,” the editorial asked, “should not the same principle be followed in peace?”

The era of demanding a “Manhattan Project” to solve this or that problem had begun.

The editorial went on to note, “There are enormous gaps in our knowledge that need to be filled,” and it selected out the following “disgraces,” among the “thousands” that existed, that could be cured if only “our niggardliness and blindness” were put aside, and a suitable scientific effort expended:

- cancer, arthritis, heart failure, and the “degenerative diseases”

- the “millions of chemical compounds,” many of “immense importance,” not yet discovered

- the inability to “predict what the weather will be a fortnight hence in Chicago or New York”

- the fact that “we have only the vaguest notion of what happens to a beefsteak after it is eaten”

It is this editorial that prompted Warren Weaver to write to the Times to challenge both its conclusion, as well as Times science editor Waldemar Kaempffert’s call for the planning of science, detailed in Pt. 1 of this post.

Weaver observed that the “planning and control” that had made the war’s scientific achievements possible had only been feasible under the pressure of the war, and that it was “wholly inconsistent with peacetime democratic procedures.” Scientists would not tolerate a similar level of control in peace.

Moreover, he argued, even if “a new generation of scientists who will stand for control” (pdf) were produced, the system would still be ineffective, precisely because the research would be too focused on producing particular results. He reflected:

the sober fact is that the great bulk of scientific work during war consists of rushing through with feverish haste and often with highly inefficient but necessary extravagance, the practical applications of basic scientific knowledge which has been gained in the past. Gained by whom, and how? Why, gained by free scientists, following the free play of their imagination, their curiosities, their hunches, their special prejudices, their undefended likes and dislikes.

Weaver emphasized that he was speaking only of “those working in pure science,” and that the “applied scientist, directing his work toward specific, immediate, practical objectives, naturally accepts certain restrictions.”

Here we reach a delicate and important point of interpretation.

One of many reflections on the “pure science” problem

One of many reflections on the “pure science” problem

Weaver’s laudatory remarks on the qualities of pure science might easily be taken to mark his adherence to a sort of ideology of pure science, which many historians have taken to have prevailed in the postwar period. According to this interpretation, the tenets of this ideology attributed a quasi-mystical quality to the workings of pure science, claimed it was fully independent of political considerations, and vastly overstated its importance as a wellspring of invention, and, thus, its role in sustaining the national economy (a false doctrine its critics have dubbed the “linear model” of technology or innovation). By propounding this ideology, its proponents laid claim to public resources (and, in some accounts, political authority) without any implied restrictions or oversight.

Now, as I mentioned Pt. 1, testimony concerning the baleful effects of the idea of pure science was already present in J. D. Bernal’s prewar calls for the planning of scientific work, and the denial of the existence of such an entity as pure science was instrumental to Kaempffert’s call for planning in the United States. So, we have to be aware that, if we simply characterize Weaver’s rhetoric as ideological, we are essentially accepting Bernal’s and Kaempffert’s criticisms as a satisfactory analysis of Weaver’s ideas.

To return to David Hollinger’s passage in Pt. 1 that inspired this post, I believe Hollinger’s paraphrasing of Weaver renders his letter more starkly ideological than it actually was. But, because historians have basically accepted the existence of this ideology, his extraordinary characterizations of Weaver’s claims may well appear plausible, as they did to Jon Agar, who is a good historian and well-versed in these issues.

But what did Weaver actually claim?

Weaver wasn’t actually that clear on what he regarded the relationship between “pure” and “applied” science to have been. He suggested that “free” scientists could work either in “austere isolation,” or “in close contact with other scientists, sometimes electing to work in cooperative teams.” It is not obvious whether this means that pure science could derive from practical work, but I think Weaver would agree with the proposition.

I agree with David Edgerton that there is no evidence that anyone ever actually believed in or advocated a naive linear model. For the case of Weaver, we can actually look at his wartime experience as director of the Applied Mathematics Panel (a sub-group of the Office of Scientific Research and Development) to get at what he must have known and understood.

First, Weaver had just witnessed the (soon to be declassified) creation of sequential analysis, a fundamental new advance in statistical theory formulated by Abraham Wald in the course of war work, and inspired by, and immediately applicable to, practical problems in quality control testing.

At the same time, Weaver may well have had in mind his responsibility for terminating Norbert Wiener’s groundbreaking wartime work on cybernetic fire-control mechanisms, which were deemed inapplicable to pressing wartime problems.

Wiener’s cybernetics did not fit the mold of wartime research

Wiener’s cybernetics did not fit the mold of wartime research

What Weaver did very clearly claim in his editorial is that pure science constitutes a resource that must be perennially replenished, lest applied science stagnate. The war, he argued, drew down that resource:

It is just as though some group of gangsters had held guns to the heads of every member of the board of directors of some great corporation and forced them to declare as dividends all the surpluses which had been earned over many previous years. The stockholders, seeing their dividends suddenly increased, are delighted. They want to see the system continued. They do not stop to think that you cannot go on declaring dividends out of surplus.

The analogy, I think, downplays the degree to which technological development mainly revolves around the improvement of existing technologies. However, if we allow that scientific knowledge is, at some ancestral level, the ultimate root of many inventions, and that, in any case, it can provoke or expedite the process of improvement, I think it’s a valid enough point that it doesn’t mark Weaver as an ideologue.

In any case, while the war did have certain productive effects on scientific development, these were mainly realized in the postwar period. During the war, many new lines of research, including those deriving directly or indirectly from war work, did not advance, or at least not very far. Weaver, recall, was reacting specifically to the claim that wartime research practices be perpetuated indefinitely. However, he clarified that his rejection of the ordinary utility of wartime organization did not mean that

science must have a completely Topsey-like development. There are gaps in the structure of science that can, at any moment, be recognized: and it is perfectly legitimate and useful for individuals, universities, foundations and Federal agencies to stimulate work in such areas by furnishing special support.

“But,” he insisted, “this procedure is healthy only when there is a multitude of such agencies, seeing with greater or lesser acuteness of vision the many different gaps; so that individual scientists are not forced against their wills to choose one special line of work, and so that the great blessing of the democratic averaging process has a chance to operate.”

In any case, Weaver argued that the “important gaps in science are ones we do not see and cannot foresee.” Thus, he rejected the calls for Manhattan Project-like initiatives to solve an endless stream of problems, as well as Kaempffert’s call for a “map” of science, overseen by what Weaver called a “super-control” that would only make money available for gaps in scientific knowledge that it had identified itself. Such schemes could never locate or support instances where a “free scientist” might “drive a brilliant wedge deep into the structure of science, splitting it wide open,” which he viewed as crucial to the long-term development of science.

Returning to Hollinger’s characterization, Weaver does say something to the effect that, during the war, “the sciences had not been advanced by government coordination at all,” so long as “science” is taken to mean “pure science,” though he was never so absolute as to imply the “at all.” To the contrary, Weaver wrote that the war had “given stirring illustration of the fertility of group approaches to certain kinds of problems.”

As we have seen, Weaver did essentially say that the OSRD was restricted to “coordinating the ‘practical application of basic scientific knowledge,'” provided we take this to mean that wartime research was predominantly in the applied domain, which had some ancestral link to basic science, and not that it was scientists constantly translating basic science into new inventions, which would be ridiculous.

Nowhere did Weaver say anything remotely resembling “The recently exploded atomic bomb was not a product of government science.”

In sum, I don’t think Weaver’s position is totally fair to Kaempffert’s, nor is it a completely accurate picture of how research operates, but, given the actual content of Kaempffert’s proposals, attendant calls for perpetual Manhattan Projects, and the nuances that Weaver did offer concerning his ideas, I don’t see the letter as the recklessly ideological hatchet job that it seems to be in Hollinger’s gloss on it.

—

I will probably eventually do a Pt. 3 of this post, discussing Kaempffert’s response to Weaver, and Weaver’s revisiting of this issue in the 1960s.